I’d first read Israel Zangwill’s book The Big Bow Mystery, a locked room novel set in the London area of Bow, not one about a big bow. The mystery itself, though ingenious, is really a skeleton to introduce outsized, entertaining characters and dialogue, an impulse which is given full expression in King of the Schnorrers.

The book is set in the Jewish communities of London at the end of the eighteenth century, a time Zangwill regards as “while the most picturesque period of Anglo-Jewish history, it has never before been exploited in fiction.” The time is introduced as one of great hostility to the Jewish people of London, with them being denied “every civil liberty but paying taxes” and the Gentleman’s Magazine having nothing but invective at the “infidel alien”. Yet the first character the reader is introduced to, Grobstock, is leaving a synagogue who had been patriotically praying for the return to health of King George and is carrying a large bag of money he has earned as a member of the East-India Trading Company. “There was no middle-class to speak of in the eighteenth century Jewry; the world was divided into the rich and poor, and the rich were very, very rich and the poor very, very, poor, so everyone knew his station.”

Grobstock is met by a crowd of schnorrers. These are beggars, but very particular ones. They don’t fein madness like the eighteenth century Abram men, nor do they fake illness or injury. Nor do they ask for alms as a favour but as a right, the Talmud instructs wealthy jews to give charitably to those who need it, so these beggars are claiming charity that is rightfully theirs. To add an element of a game to his giving, Grobstock has painstakingly wrapped differing sums of money in paper packets, giving them out to the schnorrers and delighting at their different reactions to the different sums.

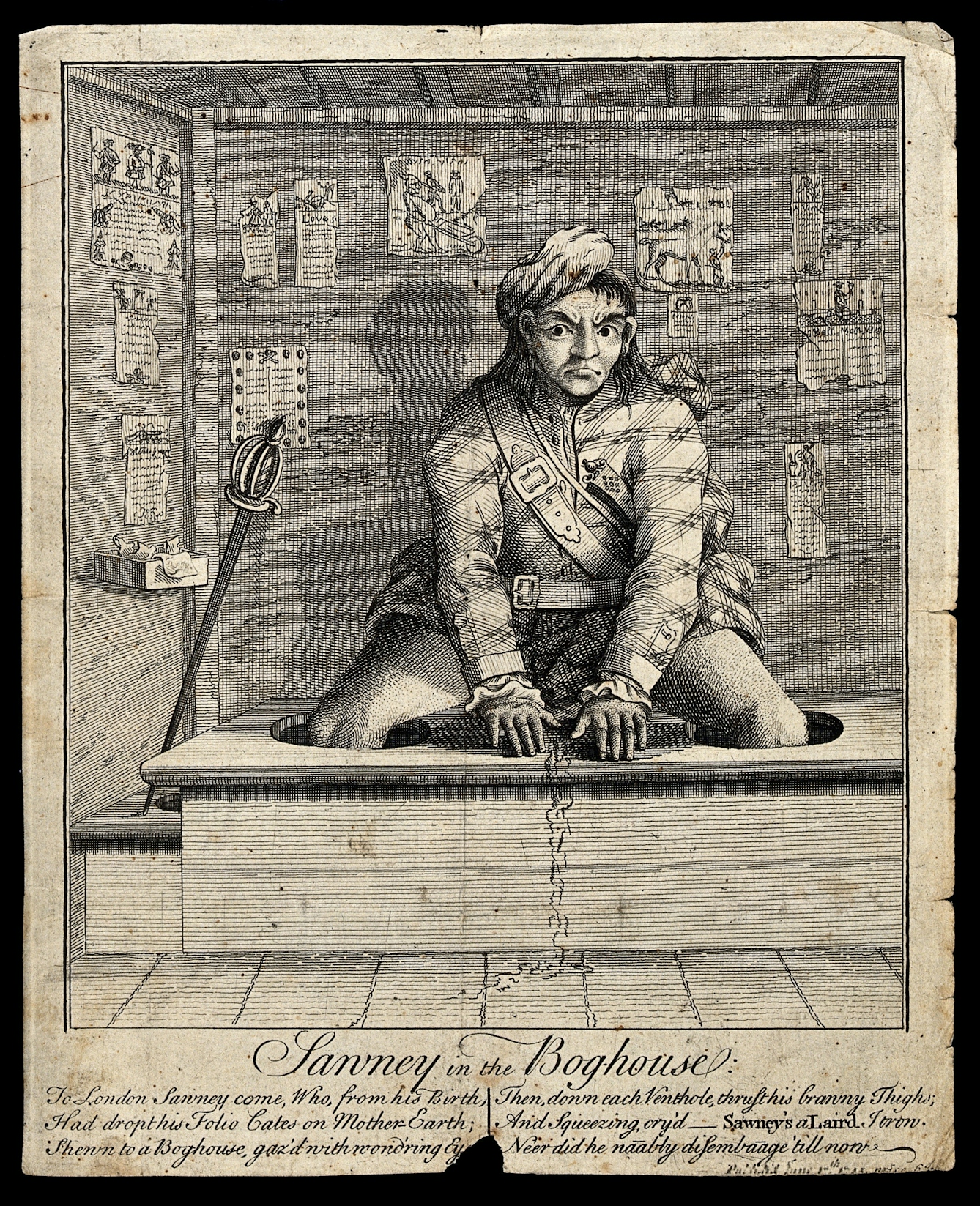

Having done this, he walks towards his house, pleased at a good deal done in a fun way. He meets another schnorrer on his way back. This man is different to the others, while they have tried to dress as Londoners, this man is dressed in an outlandish garb, with a makeshift turban on his head, a bushy, black beard and layers of clothes and scarves - a little Faginish. Grobstock offers the stranger one of his packets and, to his terrible luck, it’s the one packet with nothing in it. Rather than taking it as a joke, the stranger launches into an invective, fluent in the language of the Talmud which rather sets him back.

This figure is the hero of the book, Manassah Bueno Barzillai Azevedo de Costa, the self-styled King of the Schnorrers. One of his lines of attack against Grobstock is that Manassah is a Sephardic Jew, descended from the Jews of Spain and Portugal, where Grobstock is an Ashkenazi, descended from the ghettos of Germany and Poland (as indeed, Zangwill was). This divide between the two branches of Judaism, with their different customs, histories and Hebrew pronunciation becomes one of the big themes of the book. The Sephardic Jews have the glamour and (self appointed) nobility of the grand old courts of Granada, they came to London first and regard the Ashkenazi as gutter scum pouring in from the continent. Even as Grobstock is far richer than Manassah, there is a sense he is lesser in inheritance.

One of the joys of the book is how Zangwill portrays the sheer unstoppable force of Manassah. He is relentless, able to twist any comment or action into an insult that needs repaying, or a gift that needs taking. He is able to twist the words of Moses into any form he needs and does so with an entitlement that very few of the other characters are able to combat. It’s this picture of an immense force of personality wedded with the ability to pivot in any direction at any time. His manner of entering a room is described as “always a search warrant”. What’s more, he’s not a Bus Bunny like trickster, he never smiles and winks and seems to fully believe each pivot, each twisting of law and convention, even as he contradicts himself. Zangwill says that if he “had more humour, he would have had less momentum” and it’s the momentum of this character on everyone around him that makes the book more entertaining.

Grobstock ends this encounter poorer and, worst of all, having extended a Friday night dinner offer to Manassah. When he turns up, he has an even poorer, Ashkenazi schnorrer in his train called Yankelé. This man is more a common trickster figure, seemingly more conscious of his tricks and elisions. Through the course of the book, he manages to win Manassah’s respect and the hand of his daughter in marriage.

This is an outrage for the Portuguese synagogue. No daughter of theirs is to marry an Ashkenazi, and Manassah’s next mission is to find ways of tricking, talking and bullying them into it. On the way he manages to secure his daughter a dowry far outside of his means and a permanent pension, securing himself forever, the title of King of the Schnorrers.

This book is a fascinating, comical glance at a side of eighteenth century London that I haven’t encountered before. A world where there are members of an oppressed and very close-knit community (or rather, two communities with a power imbalance built in), who include extremely wealthy bankers, even a fashionable ‘beau’ but also poor scholars and lay-preachers. There’s a sense of a world in itself, where all the other aspects of London life are of distant importance to synagogical politics. Also interesting were the locations. There were the City banking locations, but not so much of the East End, Cable Street kinds of places, and nothing of Golder’s Green. The main centres seem to be south of the river, or way out in Hackney.

It’s also the story of a wonderful wrecking ball of a character who smashes his way through all problems. I’m glad he had a happy ending. I’m also glad I don’t have to deal with him.